|

You are here: 4Campaigns & Battles4Index4The Battle off Heligoland |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Battle off Heligoland (1864):

North Sea Squadron

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The screw propelled frigate NIELS JUEL, commanded by commander Johan L. Gottlieb, had been stationed in Skagerrak since the end of January 1864 to watch for three Prussian gunboats rumored to be in the North Sea. When war broke out on February 1, the Commander received orders to leave the Norwegian coast and reposition himself in the Norts Sea between Borkum and Heligoland. Shortly after that, NIELS JUEL was ordered to expand its operational area to Falmouth in the English Channel. The assignment was to watch for Prussian warships, but after the outbreak of war, the assignment was expanded to include the capture of every German ship it might meet. German indignation |

Commander

Johan L. Gottlieb |

The presence of the Danish frigate NIELS JUEL in the North Sea and the English Channel created a furor among German shipowners, who feared the capture of their ships!

|

However, poor weather in the North Sea forced the frigate to return to port in Copenhagen after suffering weather-inflicted damage. The frigate was replaced by the corvette DAGMAR, under the command of Lieutenant Commander G. F. W. Wrisberg. The Danish blockade would soon prove to be every bit as effective as the blockade in the First Schleswig war of 1848-50. On March 18, 1864, the corvette succeeded in capturing the Hamburg schooner TEKLA SCHMIDT off Texel in the North Sea. |

The screw propelled corvette

DAGMAR. |

The corvette also functioned as advanced observation post in the North Sea.

The North Sea Squadron

At the beginning of March 1864, the Secretary of the Navy received intelligence suggesting the Austrians were assembling a large naval force.

Its purpose was to try, with the Prussians, to break the effective Danish naval blockade.

This resulted in a decision by the Secretary of the Navy, to establish immediately a North Sea squadron. The squadron was made up of the corvette DAGMAR, which was already in the area, the frigate NIELS JUEL and the propeller-driven HEJMDAL, which was in Copenhagen. The Secretary of the Navy appointed Captain Edouard Suenson to command the squadron.

On the morning of April 4, after repairs were completed, the NIELS JUEL and the HEJMDAL departed from Copenhagen. Scarcely an hour after their departure the Secretary of the Navy received a telegram with the information the Austrian frigate RADETZKY had left Gibraltar and was heading north.

Edouard Suenson

|

The Secretary of the Navy's choice of Captain Edouard Suenson as squadron commander was hardly a coincidence. Suenson, as commander of the paddle wheeler HEKLA had already earned both honor and battle experience in the first Schleswig war of 1848-50, particularly in the battle of Neustadt, July 20, 1850. A month later, he took part in a skirmish between the HEKLA and the LØWE, and four Schleswig-Holstein gunboats in the Kiel Fjord. Also, Suenson had gained valuable expe-rience serving in the French Mediterranean fleet in 1830. To Norway |

Captain

Edouard Suenson

|

Sailing through heavy seas in the Kattegat, the two Danish ships arrived in Kristianssand, Norway on April 8. Their expectation was to join with the corvette DAGMAR, thus completing the squadron.

As the DAGMAR was not in Kristianssand, Suenson took this as a sign the Austrian warships were no longer in the North Sea. The Secretary of the Navy later confirmed this assumption.

The heavy seas on the voyage from Copenhagen had changed to fair-weather as the squadron sailed south from Kristianssand on April 9 to join with DAGMAR in the North Sea. The squadron would be ready to confront the Austro-Prussian squadron as soon as it appeared.

On April 11, the squadron made contact with the corvette. Commander Suenson's squadron was complete and ready to carry out its mission.

As of yet, there was no sure information of the Austro-Prussian fleet’s whereabouts. Telegrams arrived constantly relating the progress of its voyage north from Gibraltar.

Under Russian flag

Suenson used the available time to secure his supply lines and to, above all, make sure he was able to get the necessary amount of coal for his ships. In addition, training the necessary orders for the imminent battle began.

At the same time, the squadron upheld the blockade against the German harbors, and attempted to seize several suspicious vessels.

The blockade was now so effective, that many token deals were made with trading vessels to sail under Russian flag to avoid the Danish blockade.

Often a ship would be seized only to find that it had recently been taken over by a Russian pro forma firm. This increased the difficulty of effectively blockading the German harbors.

Lack of intelligence

In the last days of April, Suenson still lacked concrete information of the precise whereabouts of the enemy and its strength. It was certain, that it had not yet reached the North Sea.

News that Dybbøl had fallen on April 18 reached the fleet and did nothing to improve the humor of the Danish squadron.

The corvette DAGMAR left on the afternoon of April 19, sailing to the West towards Texel while HEJMDAL sailed for the mouth of the Elbe to seize a ship.

Now, Suensson received news that two Austrian frigates had departed from Brest on the 18 or 19th, and the Austrian ship-of-the-line, the KAISER, was expected during the next week.

Well aware the Danish corvette would be lost if it met a superior Austrian force, Suenson decided to follow the DAGMAR to reunite his squadron.

On the way, the NIELS JUEL succeeded in contacting HEJMDAL, which was forced to stop its attempt to board a German ship and join the NIELS JUEL. Together they set off at top speed to catch up with the DAGMAR.

At dawn, the DAGMAR was sighted on its way in to the Dutch port of Den Helder. In the course of the afternoon, the squadron was once again intact and on its way back to Heligoland.

The commander of the DAGMAR, lieutenant commander G. F. W. Wrisberg, had the information that he had in Nieuwediep observed two Prussian gun boats, the BLITZ and BASILISK and the paddle-wheeler the ADLER which the navy had been seeking since January.

Back to Kristianssand

April 21, the squadron was back at Heligoland only to learn there was no new information or instructions from the Secretary of the Navy.

The squadron command learned through a private telegram, that Als had been overrun rapidly, and it was uncertain the Secretary of the Navy was able to contact the North Sea squadron.

On-board the squadron, there was speculation on whether the naval firepower could be put to better use defending the Baltic and the belts as the Prussian troops pressed forward.

The lack of intelligence made decision-making difficult. The information the squadron did receive was often conflicting. Considering this, Edouard Suenson called his three commanders to a war-council on-board the NIELS JUEL.

Here, the decision was made to withdraw to Kristianssand to establish a reliable contact with the Secretary of the Navy. The location was also well suited as a base from which the squadron could carry out its tasks without being cut off from retreating, should it be necessary.

At eight in the morning on April 23, the North Sea squadron dropped anchor off Kristianssand. Immediately after that, a telegram was sent to the Secretary of the Navy. This done, the squadron began to re-supply itself with, in particular, coal to be ready to sail at short notice.

News from the Secretary of the Navy

In Copenhagen, the Secretary of the Navy, before receiving Suenson's telegram, still believed the North Sea Squadron was in position off Heligoland. The Secretary had no knowledge of the intelligence service's total failure in this situation.

The Secretary of the Navy was now able to inform the squadron the two Austrian frigates had not yet left Brest. Also, the second detachment of the Austrian squadron, including the man of war KAISER, was still close to Lisbon.

.jpg)

The Secretary of the Navy decided the

frigate

JYLLAND,

a sister-ship to

NIELS JUEL, was to

reinforce the North Sea squadron.

(Photo: Archives of

the Royal

Danish Naval Museum)

At the same time, the Secretary of the Navy advised the propeller driven frigate JYLLAND, commanded by P. C. Holm would join the North Sea force as reinforcement. This was good news but, curiously, the squadron was told the corvette DAGMAR was to withdraw.

Later, Suenson received orders to patrol a line stretching from Kristianssand to Hanstholm until the JYLLAND arrived from Copenhagen.

Waiting for JYLLAND

In the days that followed, the squadron continued to patrol the area between Hanstholm and Kristianssand, while waiting for reinforcements from Copenhagen.

|

On April 28, the corvette DAGMAR received orders to sail for her homeport. Suenson was ordered to expand his area of operations to the south as the two Austrian frigates were reported to have left Brest, but were still in the English Channel. NIELS JUEL and HEJMDAL continued patrol-ling the area while periodically picking up supplies in Kristianssand. April 30, the squadron commander received information the two Austrian frigates were now off Dover. On May 4, after the squadron had picked up supplies in Kristianssand, including coal and water, a warship was spotted on the horizon. |

Commander of the

JYLLAND,

|

It proved to be the long-awaited frigate, JYLLAND.

Captain Holm, commander of the JYLLAND, had new orders with him ordering Suenson, to sail south to The Bay of Heligoland immediately to seek contact with the Austro-Prussian squadron.

Heading south

|

May six, 1864 the united North Sea squadron, consisting of the frigates NIELS JUEL and JYLLAND, and the propeller-driven corvette HEJMDAL, sailed south towards Heligoland bay. Their mission was to resume the blockade of the German harbors, and, if necessary, try to stop Austro-Prussian squadron. Many sources could confirm the first detachment of the Austrian squadron, under the command of captain Tegetthoff, had already arrived. It had joined forces with the three Prussian gunboats in Texel. The united Austro-Prussian squadron, consisting of the two Austrian frigates SCHWARZEN-BERG and RADETZKY, the Prussian gunboats, BLITZ and |

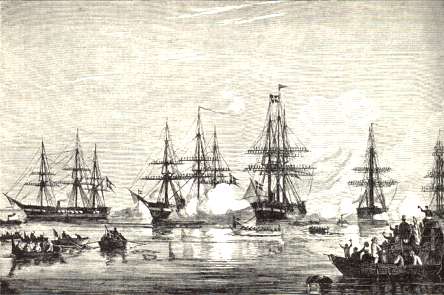

The North Sea squadron in battle line, |

BASILISK and the paddle wheeler ADLER, were now in position in Cuxhafen.

Problems

All through the night the Danish squadron sailed south through the North Sea at full speed.

Saturday morning, May 7, the HEJMDAL signaled that her port boiler was leaking.

The timing could hardly have been worse. The squadron was forced to reef the sails and wait while the crew of the HEJMDAL worked feverishly to repair the damage.

Luckily, the crew succeeded and twelve hours later, the Danish squadron continued southward.

On arriving in the Bay of Heligoland on May 8, a steam frigate was sighted. JYLLAND investigated and found that it was the British frigate AURORA.

As of yet the Austro-Prussian squadron had not been sighted. However, according to the commander on the North Sea islands, lieutenant commander O. C. Hammer, the enemy's ships had been observed in the area.

Where was the Danish squadron?

The Austrian squadron commander, captain Tegetthoff, was in the same situation as his Danish counterpart; after joining with the three Prussian ships in Cuxhafen, he still lacked reliable information about the situation in the area.

He was forced to make daily patrols just to be certain no Danish ships were in the area. On May 7, a frigate was sighted and thought to be Danish. It turned out to be, once again, the British frigate AURORA.

On the morning of May 9, the squadron was returning to Cuxhafen from a reconnaissance patrol when it received information the Danish squadron had been sighted in the area around Heligoland.

Immediately, the Austro-Prussian squadron, in line formation, sailed north in an attempt to break the Danish blockade.

Enemy in sight

A total ceasefire will take effect on May 12. This was the message from the peace conference in London. However, this message had not reached the two opposing squadrons on the morning of May 9, 1864 as they rapidly closed in on one another.

|

At dawn on May 9, the bay lay calm in the early morning light. A light breeze was blowing from the south-east. A few fishermen could be seen tending their nets as the Danish squadron approached from the north. Around ten a.m., the watch on-board the NIELS JUEL spotted a ship close to Heligoland. Once again, it proved to be the British frigate AURORA. Shortly after that, the watch spotted five more ships approaching from SSW. The two lead ships were identified as frigates whereas the three others proved difficult to identify. No doubt remained the enemy was in sight! The Danish crews were ordered to eat and change to battledress. Then Suenson ordered the squadron's ships to close quarters with the NIELS JUEL, and held a short speech for the crews. |

Commander of the North Sea squadron, captain Edouard Suenson, here seen on-board the NIELS JUEL during the battle of Heligoland. |

"There you have them, men; the Austrians. Now we meet. I trust we will fight as bravely as our brave comrades at Dybbøl!"

After that, the Danish ships prepared for battle and formed a battle line as had been ordered. The frigate NIELS JUEL lead the line as the squadron's flagship.

Ready for battle

The two squadrons were of nearly equal strength in that the Austrian cannon were slightly superior to the Danish cannon. It was impossible to predict the results of the coming battle.

The situation would have been different had the Secretary of the Navy chosen to let the corvette DAGMAR remain. Suenson, with four ships at his disposal, would have had a clear advantage, and the results would have been given in advance.

As it was, the two squadrons were of nearly equal strength when they met off Heligoland on May 9, 1864. Neither force could be certain of victory.

Open fire!

|

At 1345 hours, the Austrian frigate SCHWARZENBERG opened fire on the Danish ships from about twelve thousand one hundred thirty-eight feet. Suenson waited until the enemy was much closer before giving the Danish ships orders to fire. To begin with, the Austrians kept to an easterly course as though their intent was to pass around the front of the Danish battle line. The Danish squadron countered this move by turning to port, forcing the Austrians back to the opposite course. The squadrons exchanging fierce volleys passed one another at approximately 5900 feet. Suenson noticed the three Prussian gunboats had fallen behind the rest of the fleet and tried to break the enemy’s battle line. |

The white ships are Danish, the Austrian and Prussian, black. The roman numbers indicate the simultaneous positions of the opposing forces during the various phases of the battle. |

Tegetthoff quickly noticed the imminent danger, and turned to starboard. This brought his ships line abreast of the Danish battle line. They could now pass at close quarters, and possibly try to board the enemy.

Intense battle

The three Danish ships, keeping a tight line-ahead formation, received the Austrian ships with a fierce barrage of fire, forcing the Austrian squadron commander to change course.

The distance between the two squadrons was now down to 1300 feet. At the same time, the Danish fire increased in intensity.

The two flagships, NIELS JUEL and SCHWARZENBERG, fired on one another, while JYLLAND and HEJMDAL concentrated on the Austrian frigate RADETZKY. The Prussian gunboats remained so far away that their fire had no effect whatever.

In this way, the Danish squadron was able to achieve superior firepower, resulting in the SCHWARZENBERG catching fire twice. A large number of cannon were destroyed and the list of dead and wounded grew steadily.

On the Danish side, JYLLAND was the hardest hit. An Austrian shell exploded close to cannon no. nine killing or wounding the entire gun crew.

Hour of decision

The turning point of the battle came at 1530 hours when a shell exploded in the middle of SCHWARZENBERG’s foretopsail. The explosion ignited the dry sailcloth and rigging which caused the fire to spread rapidly.

On-board the SCHWARZENBERG, the fire proved impossible to stop as the ship’s pump had been destroyed during the battle. The damage forced Tegetthoff to disengage and seek neutral English territory by Heligoland.

RADETZKY placed itself between the burning SCHWARZENBERG and the Danish squadron, thus protecting it from further damage.

Suenson gave immediate orders for his ships to pursue the retreating Austro-Prussian squadron. However, just at that moment a shell exploded in the commander's cabin aboard the JYLLAND and damaged the ship'ss steering gear. The damage was quickly repaired, but the short delay had been enough to give the enemy a decisive lead.

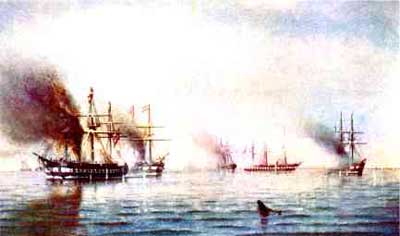

The Austrian frigate SCHWARZENBERG (to the left in the painting) is on

fire

and turning, while RADETZKY moves in to provide cover.

(Painting by

Lieutenant H. J. Marcher)

Thus, the Danish squadron lost the possibility of cutting off the enemy's retreat to neutral territory, particularly as the English frigate AURORA placed itself between the two forces.

At 1630 hours, the battle was over and Suenson ordered his squadron to the north-east to observe and lie in wait for the enemy.

Victory or draw?

Later, however, under the cover of darkness, the mangled Austro-Prussian squadron succeeded in returning to Cuxhafen and avoiding the Danish squadron.

|

In the following, the question was asked whether the battle’s outcome could be considered a Danish victory or if it had ended in a draw! The fact is, the Danish navy succeeded in upholding its blockade against the German harbors. Based on this fact, the battle of Heligoland was beyond a doubt, a tactical Danish victory. It had forced the enemy force to retreat to |

The Austrian flagship, the frigate |

neutral territory in such a condition that it was out of action for many days after the battle.

Shortly after the battle, Suenson was ordered to sail to Norway, as a ceasefire was under way. The temporary truce between Denmark and Prussia took effect on May 12, 1864. After that, the Danish blockade was raised.

The battle had cost Denmark 14 dead and 55 wounded. The Austrians had lost 32 men and had 59 wounded. The Prussians suffered no losses.

When the Danish squadron left the Bay of Heligoland, it once again passed by Kristianssand, where the sailors who had died in the battle were buried.

This was Denmark’s last naval battle involving direct ship-to-ship combat.

A hero's welcome in Copenhagen

In Copenhagen there was no problem interpreting the outcome of the battle: It was a Danish victory!

A victory the sorely tried nation needed.

When the North Sea squadron returned to Copenhagen after the battle, its arrival was celebrated in genuine Copenhagen style, including a visit from the king.

The North Sea squadron in Copenhagen after the Battle of Heligoland. The ships fire a salute, and the crews man the riggings during the King’s visit on board.

|

Sources: |

||

|

& |

Flåden gennem 450 år, edited by commander s.g. R. Steen Steensen, Martins Forlag, 2nd edition, Copenhagen, 1970 (ISBN87-566-0009-7) |

|

|

& |

Fra TREFOLDIGHEDEN til fregatten JYLLAND, y commander s.g. R. Steen Steensen, published by Thomas Schmidt A/S, May 1971. |

|

|

& |

Fregatten JYLLAND - Fra orlogsværft til museumsdok, edited by Finn Askgaard, Forlaget Devantier, Naestved, 1996 (ISBN 87-985521-3-9) |

|

|

& |

Fregatten JYLLAND i krig og fred, edited by P. A. Feldthusen & Alfred Jeppesen, Gyldendalske Boghandel, Copenhagen, 1944. |

|

|

& |

Nordsø-eskadren og kampen ved Helgoland den 9. maj 1864, by O. Lütken , Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag, Copenhagen, 1884. |

|

|

& |

Vor Flaade i Fortid og Nutid, vol. I & II, by Halfdan Barfod, Nordiske Landes Bogforlag, Fredericia, 1942 |

|

|

& |

Vor sidste kamp for Sønderjylland, by Axel Liljefalk & Otto Lütken, 3. oplag, H. Hagerups Forlag, Copenhagen, no year |

|

|

44You are also referred to the Naval Bibliography |

||

![]()

- Do you miss a major event on this Site,

or do you hold a great story?

Are you able to contribute to the unfolding of

the Danish Naval History,

please

e-mail

me, enclosures are welcome.

Please remember to list your sources.

You can also use the Naval Web Forum on this web-site.

![]()

|

MORE IN-DEPTH STORIES FROM |

|

The Battle for Als (1864) - The Battle off Heligoland (1864) |

|

THE TOPIC STORIES: |

|

- Wars against England (1801-1814) - Reconstructing the Navy (1814-1848) - The 1st Schleswig War (1848-50) - The interim War Years (1850-64) - The 2nd Schleswig War (1864) - The long Period of Peace (1864-1914) - The Navy during the 1st World War (1914-1918) - The Interim Years (1919-1939) - The Navy during the 2nd World War (1939-1945) - The Cold War Period (1945-1989) - |

|

SEE ALSO: |

|

- |

-

This page was last updated: -

This page was first published: August 1, 2006

Copyright © 2013-2016 Johnny E. Balsved - All rights reserved - Privacy Policy

_midi.jpg)